Purpose-Driven Taxonomy Design

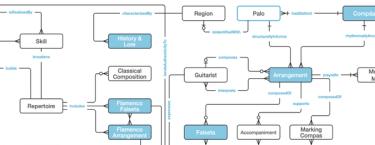

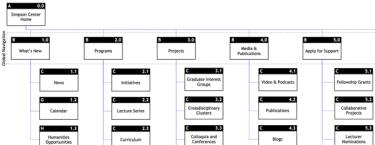

A purpose-driven taxonomy is designed to meet a clearly defined set of goals and use cases. This sounds obvious, but it's a step many organizations gloss over—often with frustratingly mixed outcomes as a result. In this article, I'll discuss a process I use for selecting terms, creating structure, and vetting design approaches on both small and large scale taxonomy projects. I'll also offer advice on where LLMs do—and don't—fit into a purpose-driven taxonomy design workflow.