A Cognitive Sciences Reading List for Designers

If you’ve ever done any contextual inquiry or usability testing, you’ve probably observed first hand the difference between what people say they will do and what they actually end up doing. Overlooked calls to action, bizarre navigation paths, mind-bogglingly irrational decisions — even the most sensible seeming users occasionally (or often) do things that “rationally” make little sense.

Which is to say that we all, on occasion (or often) do things that seem to make little rational sense.

And yet, on a day-to-day basis, this is how we successfully negotiate the complexities of our world. We use heuristics (aka rules-of-thumb) and limited information to make decisions about how we live our lives, and we do it continuously throughout the day — often without stopping to consider why we choose one thing over another.

In order to get a better sense of how our often erratic decision making processes work behind the scenes — and better understand why they sometimes don’t — I’ve been doing more reading lately into cognitive science and decision making. This post is a quick roundup of the books I’ve found most enlightening to the task of designing information systems for messy, irrational humans.

Embodied & Distributed Cognition

There’s been a lot of attention given lately to the idea that “thinking” doesn’t take place solely in the space between our ears. Modern notions of cognition understand thinking as a process that crosses into the body and spills out into the world. For a deeper understanding of how thinking is embodied and distributed, these texts are a good place to start:

Beyond the Brain

Louise Barrett, 2011

Theme

It is an error to assume that complex behavior and complex cognition are necessarily linked and that the one can only arise from the other. By understanding how brains, bodies, and environment are connected, we can better understand how intelligent, adaptive behavior is produced.

Key Concepts

- “To make a distinction between perception and cognition as separate psychological processes is both arbitrary and false” (22).

- “Language is not purely for communicating, but is also a way of effecting changes in our environment that enable us to achieve more than we could otherwise” (194).

- “The real ‘problem solving machine’ is not the brain alone, but the brain, the body, and the environmental structures that we use to augment, enhance, and support internal cognitive processes” (219).

Impressions

Very readable with lots of relatable examples and relevant context. This book draws on and furthers a wide body of foundational work (Andy Clark figures in here a lot — we’ll get to him in a minute), but remains accessible to a general audience.

Proust and the Squid

Maryanne Wolf, 2007

Theme

The process of learning to read creates physical changes in the brain that directly affect how that brain works and how we think. Understanding this process (neuroplasticity) in the reading brain prepares us to better understand the changes we’re currently undergoing as we “make the transition from a reading brain to an increasingly digital one.”

Key Concepts

- The efficient reading brain — which takes years to develop — literally has “more time to think” (54).

- Contrary to spoken language, “there are neither genes nor biological structures specific only to reading. Instead, in order to read, each brain must learn to make new circuits by connecting older regions originally designed and genetically programmed for other things” (168).

- “The new circuits and pathways that the brain fashions in order to read become the foundations for being able to think in different, innovative ways” (271).

Impressions

The first part of this book focuses on the plasticity of the brain and the ways that learning to read changes it. Wolf illustrates this story with historical accounts of writing in early societies and plenty of good ol’ neuroscience. Later chapters focus more closely on reading development in children and dyslexia before returning in a brief final chapter to the effects of digital technology on how our brains work.

Supersizing the Mind

Andy Clark, 2008

Theme

What we call “thinking” often occurs only partially in the brain: much of the human cognitive process regularly criss-crosses the boundaries of brain, body, and environment. “In building our physical and social worlds, we build (or rather, we massively reconfigure) our minds and our capacities of thought and reason” (xxviii).

Key Concepts

- “Words and linguistic strings are among the most powerful and basic tools we use to discipline and stabilize dynamic processes of reason and recall” (53).

- “Gesture and speech are interacting parts of a distributed, semianarchic cognitive engine, participating in cognitively potent self-stimulating loops whose activity is as much an aspect of our thinking as its result” (133).

- “The presence of humanlike minds depends quite directly on the possession of a humanlike body” (200).

Impressions

Clark makes a compelling and provocative case for radically rethinking the way human beings perceive, think, and act in the world; for him, all of these actions are part of a single, continuous process. Clark supports his claim by drawing on a wide range of sources in linguistics, robotics, biology, and neuroscience — from which he pulls a variety anecdotes and examples that keep the text humming along. Big ideas here and intense reading; well worth the effort.

Meaning Making

Ferdinand de Saussure, the founder of linguistics, argued that without language, we wouldn’t have thought. Figuring out how we make meaning has lot to do with how we use and manipulate symbols. This field is plenty deep, but these titles will give you some practical ways to think about how “saying” and “meaning” relate:

Metaphors We Live By

George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, 1980

Theme

We have all at one time been taught to recognize a “metaphor” as a figure of speech, a particular use of language. Lakoff and Johnson argue that, to the contrary, metaphor as a linguistic expression is possible only because the human conceptual system and thought process is, at its core, metaphorically defined.

Key Concepts

- “Our values are not independent but must form a coherent system with the metaphorical concepts we live by” (22).

- Even seemingly literal expressions are often structured by metaphorical concepts which highlight some aspects of experience while hiding others (51, 149).

- Since truth is always relative to a conceptual system, and since any human conceptual system is mostly metaphorical in nature, there can be no fully objective, unconditional, or absolute truth (185).

Impressions

This book is a great first foray into the subtleties of how we use language and metaphor to construct meaning and make sense of the world. Lakoff and Johnson drive the narrative with examples out of everyday language and take the time to thoroughly explain their conclusions. This book is definitely one of my favs.

Seeing What Others Don't

Gary Klein, 2013

Theme

Insight is not the result of concentration or a proven process, but rather of learning to “restructure beliefs.” To nurture the power of insight, we must change the story we use to understand events.

Key Concepts

- “Intuition is the use of patterns we’ve already learned, whereas insight is the discovery of new patterns” (27).

- “Insights change our understanding by shifting the central beliefs — the anchors — in the story we use to make sense of events” (148).

- “Confusions, contradictions, and conflicts can work as springboards to insight. We just have to replace our feelings of consternation with curiosity” (182).

Impressions

Klein’s book is the record of his own quest to figure out what sparks insight — and to figure out what keeps us from grasping insight that is right in front of us. He explores these questions, as well as the question of how to increase the flow of insight, across scores of stories of insight achieved (and missed). Very readable, very engaging.

The Way We Think

Gilles Fauconnier with Mark Turner, 2003

Theme

Identity, integration, and imagination are the result of the uniquely human ability to “blend” mental spaces by projecting elements from one frame of reference to another. This “cognitive blending” is the core process behind the human power to construct meaning.

Key Concepts

- “Meaning systems and formal systems are inseparable. They co-evolve in the species, the culture, and the individual” (11).

- “The meanings we take most for granted are those where the complexity is best hidden” (24).

- “Language does not represent meaning directly; instead, it systematically prompts the construction of meaning” (142).

Impressions

The Way We Think provides one of the most meticulous, in depth readings of how humans construct meaning I have ever read. The examples given range from “Eureka!” moments, where we are shown the core inner workings of sudden realization and certainty, to constructions of the most banal everyday speech, revealed to contain complex operations of imaginative blending and synthesis. A less patient reader may find some of the case studies tedious, but the core framework and analytical approach offered here provides a powerful set of tools for digging deep into how we construct and communicate meaning.

Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things

George Lakoff, 1990

Theme

We organize knowledge by means of structures called “idealized cognitive models,” which account for our ability to categorize and conceptualize. These models emerge from the basic, experiential aspects of human psychology: “gestalt perception, mental imagery, motor activities, social function, and memory” (37).

Key Concepts

- “Motivation depends on overall characteristics of the conceptual system, not just local characteristics of the category at hand” (113).

- “Since we act in accord with our conceptual systems and since our actions are real, our conceptual systems have a major role in creating reality” (296).

- “Reason is embodied in the sense that the very structures on which reason is based emerge from our bodily experience. Reason is imaginative in the sense that it makes use of metonymies, metaphors, and a wide variety of image schemas” (368).

Impressions

Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things is the 500 ton locomotive of this list — and it doesn’t come with brakes. This is a big book full of big ideas, some of which you’ll follow, some of which you likely won’t. Don’t worry about it. Success means grappling with it, not defeating it. That said, there is a lot in here for the diligent reader. I’m particularly fond of chapter 17, “Cognitive Semantics.”

Decision Making

You’re a rational person, right? You make rational decisions, right? Alas, this is what everyone thinks — and we collectively have pretty varied opinions (to say the least) about what counts as “rational.” Dig these books to get some insight into why:

Predictably Irrational

Dan Ariely, 2008

Theme

Standard economic theory suggests that individuals make decisions based on carefully weighed consideration of their options. In practice, however, “rationality” is regularly eclipsed by our irrational feelings about initial states (anchors), the temptation of getting anything for free, social norms, and the outsized value we place on what we already possess (loss aversion).

Key Concepts

- “Once prices are established in our minds — even if they’re arbitrary — they shape not only what we are willing to pay for an item, but also how much we are willing to pay for related products” (32).

- “The difference between two cents and one cent is small; the difference between once cent and zero is huge” (68).

- “Our propensity to overvalue what we own is a basic human bias, and it reflects a more general tendency to fall in love with, and be overly optimistic about, anything that has to do with ourselves” (182).

Impressions

This is one of the most accessible texts on this list: Ariely writes in an easy-going, conversational style and structures all of his arguments around closely focused, often funny studies and experiments he has himself conducted with students and colleagues. His examples are great both at illustrating his points and keeping his reader engaged.

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Daniel Kahneman, 2011

Theme

We use two cognitive processes to evaluate information: a fast, always-on, but error-prone automatic system, and a more effective, analytical but effortful deliberate system. The trouble we get into is that we sometimes mistake automatic and error-prone decisions for well-considered, analytical ones — sometimes to the point of consciously making decisions that are opposed to our best interests.

Key Concepts

- Why we fail at statistics: “our mind is strongly biased toward causal explanations and does not deal well with ‘mere statistics.’ When our attention is called to an event, associative memory will look for its cause — more precisely, activation will automatically spread to any cause that is already stored in memory” (182).

- What You See is All There Is (WYSIATI): “You cannot help dealing with the limited information you have as if it were all there is to know. You build the best possible story from the information available to you, and if it is a good story, you believe it. Paradoxically, it is easier to construct a coherent story when you know little, when there are fewer pieces to fit into the puzzle. Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance” (201).

- In misunderstanding statistical possibility, we end up paying a premium (sometimes an exorbitant one) for security from unlikely events, while at the same time gambling resources regularly on equally unlikely events. Chapter 29 (and much of the book, really).

Impressions

This book is a fascinating and compelling read. Kahneman’s examples are clear and easy to follow — and their implications are sobering (if not terrifying). I’ve talked to a lot of folks who have started this book, but never quite finished it. At 400 + pages, it’s a bit longer than some other texts on this list, but I definitely recommend reading it all the way to the end — it’s all good stuff, especially if you’re trying to understand why people (perhaps including yourself) make the decisions they do in the face of uncertain outcomes.

And There You Have It

Now: I’m not going to claim that this list isn’t challenging, or that you should be able to knock these out in a couple weekends. If you’re interested in digging into the prickly problems of designing for the complex systems that crop up when we mix data, choice, and the human decision-making process, though, these books will give you plenty to think about.

Even more than that, all of them should give you additional frames of reference from which to consider the messy, human challenges we face as designers every day. Principles like Daniel Kahnemman’s “What You See Is All There Is” or Fauconnier & Turner’s “cognitive blending” will give you new ways to pop your thinking out of the “best practices” ruts you might have fallen into and look for solutions to messy human problems in the very behavior of messy humans themselves.

Bonus Paragraph: How to Read!

You, of course, know how to read. I get that. But reading work by professional research scholars — even books intended for a popular audience, as are many of these — is a bit different from reading professional or trade publications. As a grad student (in English, during which time I read a lot), I developed some habits to help me better understand, retain, synthesize, and be able to recall texts like these. Here’s what worked for me:

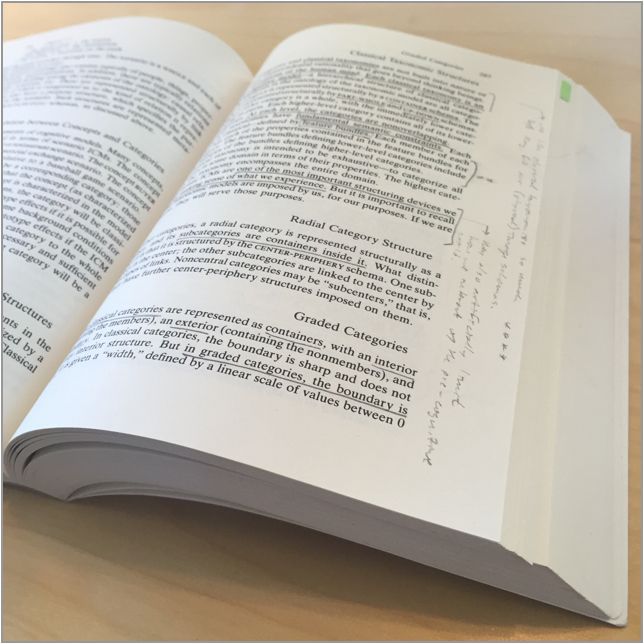

1. Buy a Book

If I’m going to read a book like one of those listed here, I want a paper copy I can write in and (slightly) abuse. The point of a physical book for me is to be able to read it actively: underline, highlight, star passages, dog-ear corners, make notes. Reading actively helps you 1) integrate what you’re reading and synthesize it with the other ideas jumbling around in your head and 2) come back to this text weeks, months, or years later and quickly find the ideas and passages that piqued your interest.

2. Buy a Pencil

Leave it in the book. If you don’t have a pencil, you won’t take notes and you won’t annotate. You’ll read passively. Set yourself up to be an active, physically engaged reader. I like a mechanical pencil like these because they’re cheap, always sharp, fit well in a book, and allow me to write satanically tiny notes.

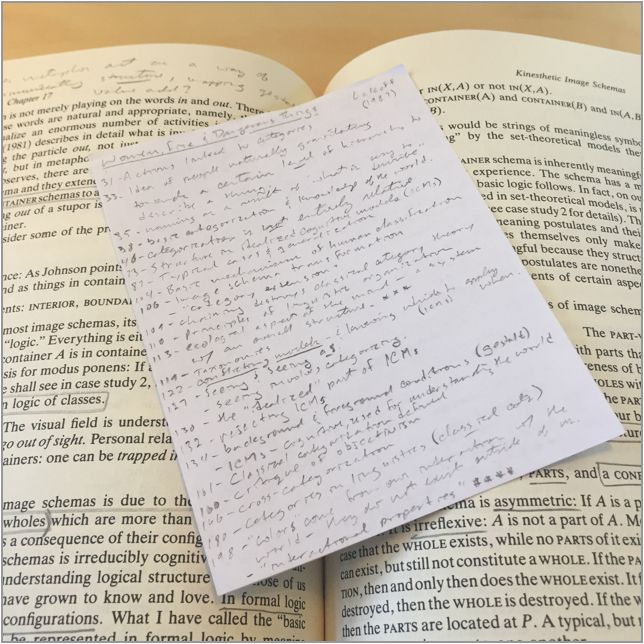

3. Steal a Sheet of Paper

Cut it in half, then fold one of your halves in half to make a booklet. Jot down the ideas and passages that stand out. I include page numbers so I can easily find passages later on. You’ll have to write small — and you’ll have to be selective about what you record (which is a good thing: too much note taking will slow you way down). Leave your notes in the book. Now when you come back and look for that idea or passage later, you’ll have both your annotations and a quick reference guide to the passages you personally found most intriguing.