Content Modeling in the Age of Flying Cars

In these heady and sometimes head-spinning few years since GPT3 appeared, those of us responsible for planning, producing, and maintaining content have had a lot to figure out. How do we ensure our content is seen, understood, and trusted now that the internet is being flooded with AI generated output? How do we get trustworthy information to audiences who prefer to use AI mediated tools like Perplexity or “AI Overviews”? How do we effectively and responsibly use LLMs in strategy and production to create higher quality content more efficiently?

In response to these and many other questions, content management system (CMS) vendors have been busy expanding their features and functionality. We now have access to built-in AI assisted idea generators and ghostwriter assistants. We have integrated machine learning based translation and personalization support for audience segments. Several tools also now have support for integrated MCP servers that connect directly to AI assistants and platform native vector stores that enable semantic search.

For the few vendors that are truly integrating these tools throughout their stack, these aren’t just incremental improvements: they’re pushing leading platforms into an entirely new category. Where traditional CMSes cater to the two dimensional flat plane of the page—what’s on the page, in what order, and what comes before and after—emerging platforms move authors beyond the familiar trappings of headings and layouts to represent facts, concepts, and ideas as richly connected entities in a defined domain of knowledge.

If one were to imagine the traditional, page-based CMS as the serviceable Ford Fiesta that got us reliably from print to online content, the emerging CMS of 2025 is the flying car of content management. These are systems free from the earthbound constraints of the flat page—with all the opportunity and all risk that that entails.

Beyond and Beneath the Page

The flying car CMS is not just a collection of bolted-on features. Platforms truly engineered for AI integration allow producers and strategists to work confidently in two new directions on an entirely new axis: beyond the page and beneath the page.

Features like personalized audience segments, automated translation, entity linking, and flexible serialization (for example to JSON-LD, llms.txt, or agents.md) are examples of working beyond the page. In many cases it still makes sense to produce pages as well, but working beyond that page means you can represent your content as richly interconnected data files, markdown, or speakable text, all with the same first class support that is traditionally given to pages.

The flying car CMS also enables you to reach beneath the page, capturing and providing granular access to the facts, concepts, and ideas that come together to form a how-to article, a product description, or an orchestrated multimedia experience. These deeply integrated AI tools give content producers production, tagging, and research superpowers—and free them from the tedious copying and pasting between fields that plagues so many existing systems.

Still Stuck in Traffic

For all the truly stunning advances we’re seeing with modern content platforms, there is one trap I see organizations fall into again and again when implementing a next generation CMS. They’ve bought the new software, they’ve integrated it with their front end, they’ve onboarded their team … but their content model includes the same constraints—and often the same structure—as their previous platform. They’ve loaded everyone into their shiny new flying car, but they’re still navigating with a paper map of roads and highways, stuck in the same gridlock they swore they were leaving behind.

How does this happen? The content model “map” is only part of the problem. Even if you’ve evaluated your content model and created a new, revised content schema in your new platform, if you’ve used the same cartographic elements you used before—the same trappings and habits of page-based design—you remain limited to the two dimensions the page affords.

If this distinction between schemas and models, or maps and cartography, sounds fussy and pedantic, let me offer two more comparisons to help you relate: Only a truly reckless pilot would take off not knowing the approach vectors, safe altitudes, and navigation aids necessary to safely land. Only a foolhardy skipper would set sail without knowing the depths, underwater hazards, or prevailing currents along their route. A roadmap has affordances for neither of these navigation contexts; aeronautical and marine charts do and afford safe passage for those who use them wisely.

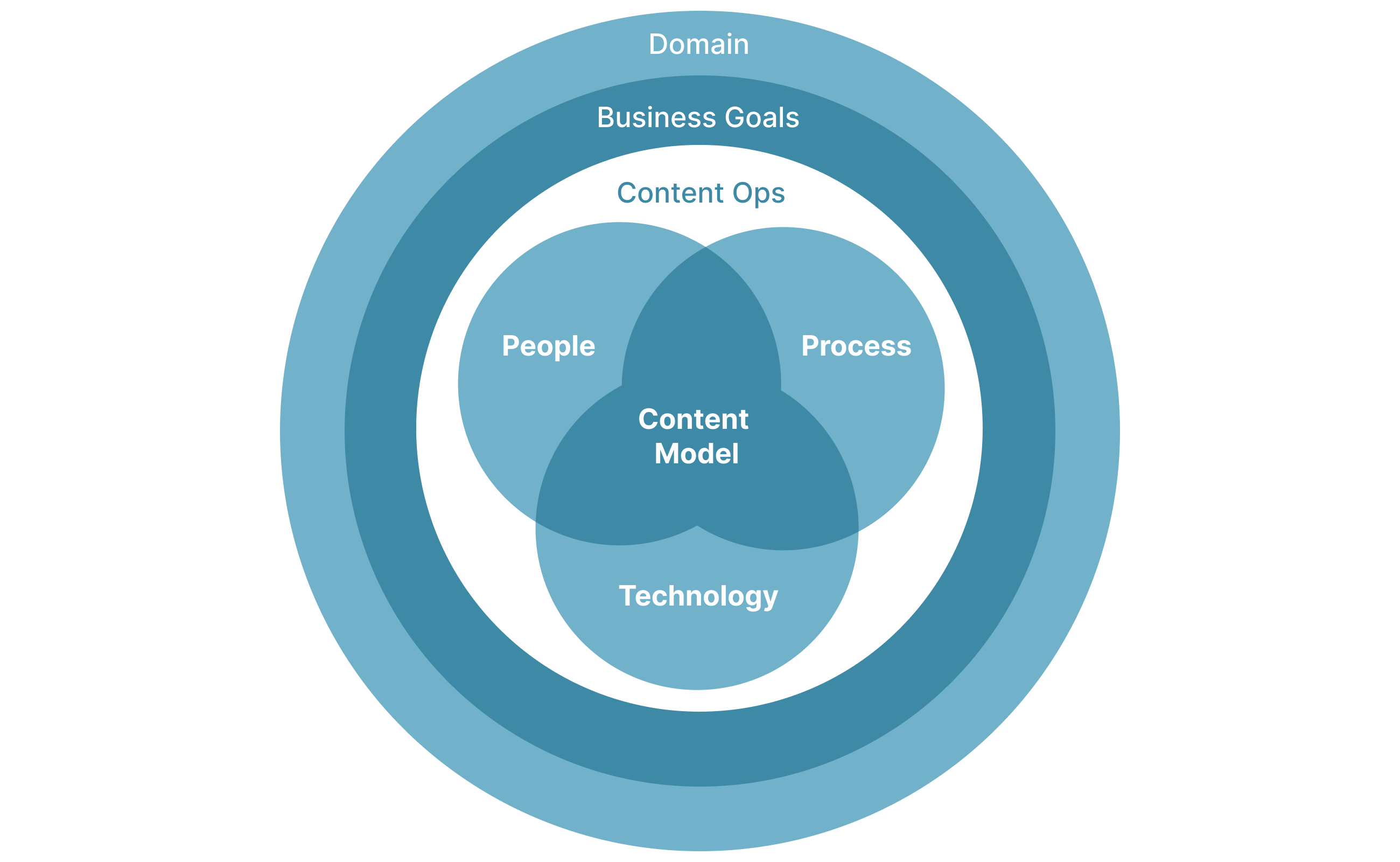

A better map, which is to say a more expressive and robust schema, begins with a more robust and expressive conceptual model. These models are achieved by stepping back from the page and identifying the facts, concepts, and ideas your pages are meant to communicate, and then modeling those elements to support the coordinated ensemble of people, process, and technology (including AI) you use to create content. This process is called Domain Driven Content Modeling.

Domain Driven Content Modeling

Every organization operates within a specific sphere of influence and activity. This is your organization’s “domain.” By aligning on and articulating the goals you’re working to achieve within your domain, you can more easily identify the relevant attributes and relationships common to your content. These are the facts, concepts, and ideas germane to the actual work you do, the “differences that make a difference” for your organization.

Every organization also produces content with a specific combination of people, process, and technology. This is your approach to “content operations.” Your content operations may include a team of 20 people using established workflows across a highly polished tech stack, or it may be one person periodically updating markdown files on a geriatric Thinkpad. If your organization creates content, you already have an approach to content operations: it's either working toward your goals, or it's working against them.

Your content model sits at the center of your content operations. It describes your organization’s content structure (types, objects, and attributes) and content semantics (the formal relationships between structural elements, taxonomy terms, and business rules). In a domain driven approach to content modeling, the design of the content model is explicitly informed by the goals your organization is working to achieve within your domain, and the opportunities and constraints inherent to your people, process, and technology. It’s an approach to content modeling that isn’t based on the formal characteristics of the pages you publish, but rather on the work you actually do.

If you create documentation for medical equipment, for example, a domain driven content model might capture set-up, operation, and troubleshooting steps for a particular machine. These are not stored as blocks of free text under generic headings, but as structured objects in a machine readable sequence associated with defined use cases and equipment models. Likewise, if you produce footwear from a range of different materials, your content model may capture provenance and cleaning information for each type of material. Descriptions for products using these materials can then draw from a central store of facts to describe where the materials were sourced and how to care for them.

Your content producers may still be composing in a page-based UI—it’s what authors know and are comfortable with—but when the underlying model is not limited by page constraints, CMS integrated AI assistants can draw on the underlying structure and relationships beneath the page to make informed suggestions, reduce time searching for information, and allow producers to focus on the activities where they produce the most value. Once produced, this content can appear both as a page and beyond that page as machine readable markup or plain text optimized for generative AI.

How to Get Started

As you can by now surmise, the first step in creating a domain driven content model has nothing to do with code. The CMS is often where the domain model is realized as a concrete entity—even in a “flying car” CMS—but this doesn’t mean its creation is an engineering task alone. In addition to meeting technical requirements, the content model should support the needs and capabilities of content producers and coordinate the requirements of your strategy, production, authorization, and publication process. Your organization’s goals within its domain drive the selection of what gets represented and at what level of granularity, and how those elements relate to other parts of the model.

Fortunately, most of the techniques for gathering this information are well established and widely available. Stakeholder alignment, process modeling, contextual inquiry, and content auditing can all provide valuable insight into the cartographic elements needed to structure a well connected, domain driven content model. Methodologies like the Structured Content Design Workflow can help you plan and stage these activities and work toward a domain-based model that allows you to work on, beneath, and beyond the page.

You also don’t need to tackle the whole model at once. The leading vendors in the “flying car” CMS space have built in affordances and workflows for change management over time. Use these to introduce a domain-driven approach in stages—and to support continued evolution once you’ve effectively moved beyond the two dimensional constraints of the page.

Whichever approach you take, consider not only the model you’re using to orchestrate your content operations at present, but also the concepts and “cartographic language” you make available to your model-building process. When it comes to managing content, the long-awaited age of flying cars is (metaphorically) finally here. We’re all still learning how to navigate these new horizons, but one thing that’s certain is that this new territory will need a new kind of map—and a fresh perspective on how we plan, build, and share the content we create.